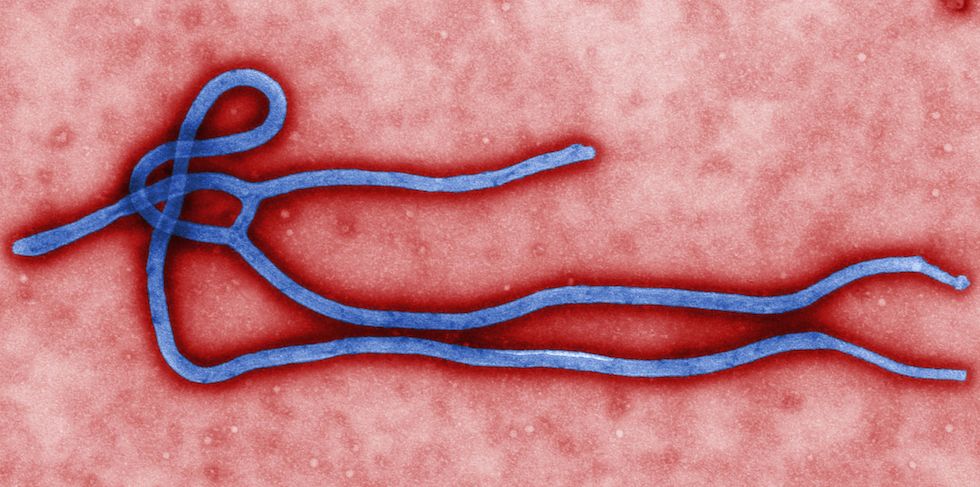

As World Health Organization (WHO) released the latest death toll on Monday for most recent outbreak of Ebola, health ministry officials in the West African region are getting more and more anxious about the possibility of an epidemic of unprecedented portions. The WHO went as far as exclaiming that the situation was « out of control », inspiring much panic in the region.

Already the disease has been unique from the previous years in that it has traveled across the borders of three countries: Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia. Numbers of the current outbreak are double that of the last most lethal outbreak during 1995 in the Congo. Climbing to 467 known deaths, health ministers from the three effected countries and 8 other West African countries met on Wednesday and Thursday for an emergency two-day summit in Accra, Ghana, to discuss strategy for essential regional co-operation.

Ebola: new challenges but a known disease

Although this outbreak has presented both humanitarian agencies and health officials with new challenges, the disease itself is nothing new to the region. Originally discovered in 1976, the sickness is believed to be hosted by the fruit bat, which is a delicacy in Guinea and Liberia. The current variation of the disease is its fifth mutation and according to the WHO, there have been 19 known outbreaks of the disease since its discovery. The reason for its almost 40 year presence is mostly due to the weak public health systems in the West African region, which, in turn, can be attributed to the relatively unstable political situations in these countries. For example, Sierra Leone and Liberia are both recovering from decades of consistent civil wars and Guinea is attempting to structure its political system after half a century of dictatorship that recently ended in 2010. The Guardian reported on Thursday that daily updates from the Liberian ministry of health are littered with examples of a poorly run heath system. One of the internal notes stated that two suspected cases were allowed to travel from a rural city in Guinea to its capital because « the county laboratory supervisor could not be found. »

In addition to the poorly managed health organizations, the uniquely challenging qualities of Ebola have made the attempt to combat its spread all the more difficult. The symptoms of the disease make it tricky to treat early on as they mirror those of malaria. However, as the illness progresses beyond stages susceptible to treatment, the symptoms take a horrific turn. Victims have been reported to have heinous internal and external bleeding with the majority of deaths caused by shock or multiple organ failure. It has a fatality rate of about 90% and no cure currently exists for the disease; however, if sufficient treatment is received early on the chances of survival increase significantly. As if the disease was not already terrifying enough, it is infamous for its high contagion rate. Nurses and family members are usually the first ones to acquire the disease, as it is most infectious when patients are already dead. Those handling the bodies after death (for funerals for example) are most likely to contract the disease.

Mistrust and misinformation have enabled rapid proliferation

In spite of all of its alarming qualities, what makes this disease the most dangerous is the way it interacts with the cultures that it has infiltrated. Its transmission has been dramatically accelerated by cultural practices, a public distrust towards authority, and extremely mobile populations. The Kissi ethnicity found in all three countries follows a burial practice in which the dead are traditionally kept at their home for several days as mourners visit the family and touch the deceased’s head before burial. Thus the practice poses an enormous challenge for humanitarian agencies attempting to limit the spread of the disease. Organizations like Doctors Without Borders have resorted to having nurses in full biohazard gear bury the dead, which is unthinkable to some grieving family members.

In addition, widespread mistrust of professionals and humanitarian agencies and misinformation regarding Ebola have complicated treatment and enabled rapid proliferation. Initially, people in Sierra Leone regarded the outbreak as a government conspiracy to depopulate Sierra Leone’s Kaliahun district. In Liberia, residents believed the epidemic was a « hoax » created by government officials seeking to distract citizens from a series of recent scandals and for health officials to seize public funds. In Guinea, a popular text message spread that claimed an antidote to the disease could be found by mixing hot chocolate, coffee, milk, raw onions, and sugar.

The rampant distrust has fueled violent resistance to the arrival of health workers to treatment centers. Doctors Without Borders has reported that they are 20 villages that they are unable to work in due to the hostility towards their staff. Similarly, the Red Cross announced on Wednesday that it was unable to continue its work in southern Guinea due to inhabitants threatening staff with knives. Moreover, doctors have begun complaining of patients escaping treatment centers to visit traditional healers who often end up contracting the disease and spreading it to their other patients. One doctor lamented in an article, « When you have patients disappearing like that, you don’t know where the virus will appear next. » This is further intensified by the extremely high mobility of these populations causing the disease to be spread across borders from heavily forested and rural areas to all three countries’ densely populated capitals.

As a result, the governments of Liberia and Sierra Leone issued warnings on Monday announcing that anyone thought of keeping Ebola patients in homes or churches would be prosecuted. The government of Liberia has attempted to dispel misinformation that the Ebola cases are hoaxes by putting terrifying images of infected patients in newspapers and on television. Additionally, in response to warnings from the WHO of possible travelers carrying the illness to bordering countries, Senegal has closed its border with Guinea.

Although there have been many efforts on behalf of the health ministries and governments of the three countries to combat the many challenges the outbreak poses, the summit revealed a few things that must be done to avoid total catastrophe. The summit concluded with officials agreeing that more money was needed urgently for drugs, basic protective gear for health workers, and staff pay. A Liberian district health officer, Philip Azumah, was quoted saying the international community was crucially needed to aid the three countries to get information out regarding the disease. Azumah stated that there needed to be a massive information campaign that should involve community leaders, local and national media not just professional experts. It is clear that an increased awareness of the disease and trust in authority is vital in order for Ebola to be contained and eradicated. If the international community is not quick enough to help these struggling countries, it is not out of the question to imagine Ebola as a global problem.